Transparency to the max: Why one lawmaker handed over to me 142,675 emails

State Sen. Graig Meyer is fed up with his colleagues for inserting a last-minute provision into the state budget allowing lawmakers to sell and destroy communications as they see fit.

To view this newsletter in full, please click on the headline or visit the Anderson Alerts website. Please allow me to put today’s edition in the proper context:

This story has been months in the works and remains an ongoing project. While it doesn’t have all the answers, it sheds light on new provisions that allow state lawmakers to sell, destroy and disclose communications as they see fit— a major blow to a public that deserves to know what elected officials are up to, how tax dollars are being spent and forces driving decisions in Raleigh behind the scenes.

I’ve likened North Carolina’s revised public records law to a marathon. What do I mean by that? Asking a lawmaker to voluntarily disclose information potentially at their own expense is like asking me to run a marathon. Is it theoretically possible? Yes. Is it likely to happen? No. And even if it does happen, it’s going to be a long, painful journey to get there.

It would be hypocritical of me to write this in-depth piece on transparency without also being transparent myself. As such, I am making this post publicly available to all readers.

If you find this story useful, please consider upgrading to a paid membership, giving a gift subscription or telling your friends to subscribe to Anderson Alerts. Thank you for your continued help in making this reporting possible!

To subscribe or update your membership, you can visit this page. And if you want a chance for a complimentary all-access membership through the November election, you have until noon on Thursday, March 21 to submit your March Madness bracket here to the Anderson Alerts group.

Now to the story…

It was a Friday morning at North Carolina Central University where one lawmaker stood uncomfortably to accept an award.

Democratic state Sen. Graig Meyer of Orange County was happy to be recognized by the NC Open Government Coalition for his work encouraging transparency in the legislature, but he was also deeply disappointed to find himself on an island.

Meyer is one of a small handful of state lawmakers willing to disclose internal communications following the passage of a state budget that included last-minute changes. The changes have allowed current and former lawmakers to control their own records and sell and destroy their communications as they see fit.

“It's so dumb,” Meyer said of his award. “Why should a legislator get an award for public access when this should be the baseline?

“I appreciate the award and I appreciate the Open Government Coalition's recognition. It's just so paradoxical because it highlights how difficult this important work is that you have to give an award for somebody who's just trying to do what we should consider the baseline of acceptance for being a public servant.”

In his acceptance speech at the March 8 event, Meyer described an action he would take later that day. Hours after accepting his award at the North Carolina News & Information Summit, Meyer did something no lawmaker had done to date: He handed me a flash drive with 142,675 emails dating back to 2014.

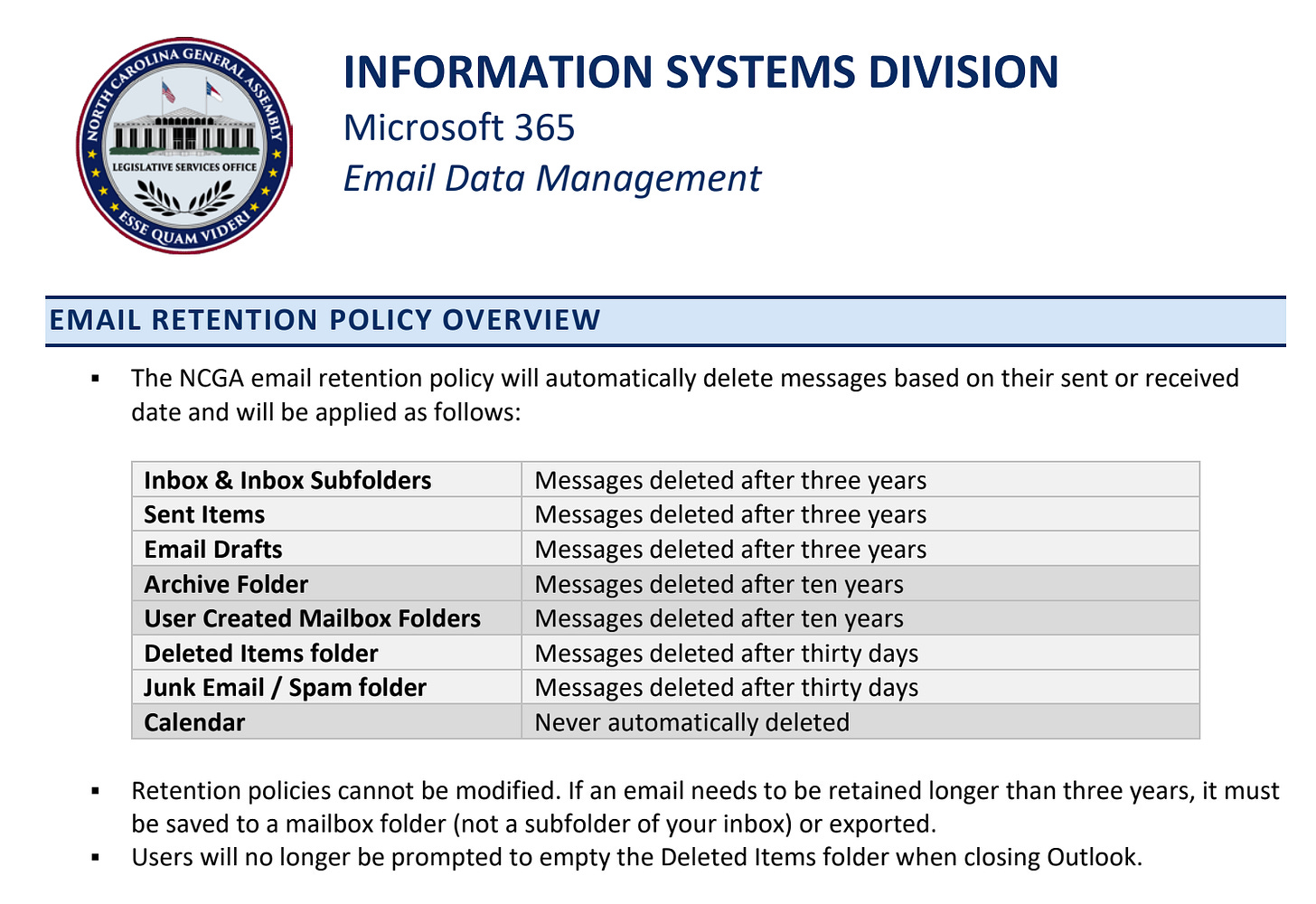

The move came in response to a sweeping public records request I made six months earlier and before the state budget had taken effect, where I asked all 170 state lawmakers to disclose their communications to the greatest extent possible.

None of the 102 Republicans in North Carolina’s General Assembly have turned over a single document to me, while just six of 68 Democrats have shared at least some of their communications (Meyer, Sen. Dan Blue, Rep. Wesley Harris, Rep. Deb Butler, Rep. Marcia Morey and Rep. Mary Belk).

The Raleigh News & Observer also made a narrow request of lawmakers. The result: Just 33 (10 Republicans and 23 Democrats) sharing any communications. Over 130 lawmakers ignored the request completely.

“As a legislator, it makes me sad because I'm so disappointed in my colleagues for not having principle on this,” Meyer said of the abysmal response rate. “As a citizen, it makes me angry that people are elected to office who won't allow the public to access the records of the business that we elected them to do.”

A handful of additional Democratic and Republican lawmakers or staff members have responded to my request, but they’ve either asked the request to be narrowed or voiced concerns about sharing constituents’ personal information. (It’s also worth noting that I made a substantially narrower request of all lawmakers on the budget conference committee for three days worth of emails that few have responded to.)

So for this edition of Anderson Alerts, let’s dive deep into how lawmakers gave themselves the unilateral authority to withhold public records, what information I requested, why Meyer agreed to be a case study, what was learned from the experience and whether anything will change.

The process

At 1:14 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 18, 2023, state lawmakers produced a draft budget proposal that was leaked to reporters.

Buried deep within it was a major blow to transparency.

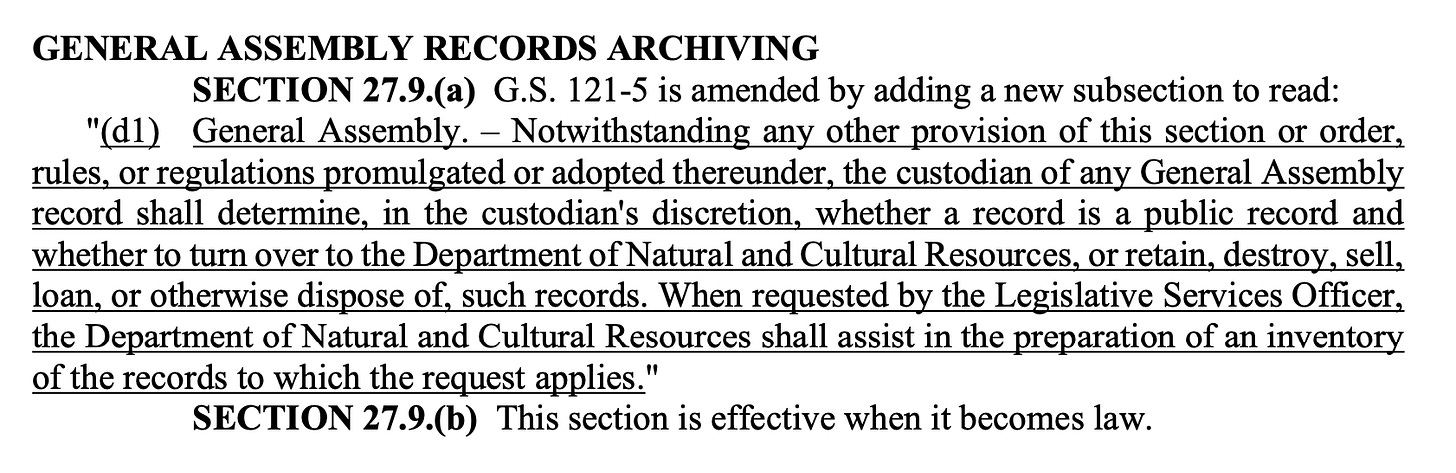

A provision read, “Notwithstanding any other provision of this section or order, rules, or regulations promulgated or adopted thereunder, the custodian of any General Assembly record shall determine, in the custodian's discretion, whether a record is a public record and whether to turn over to the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, or retain, destroy, sell, loan, or otherwise dispose of, such records. When requested by the Legislative Services Officer, the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources shall assist in the preparation of an inventory of the records to which the request applies."

Transparency advocates pushed back on the provision.

“Interpreted broadly, this language gives total discretion over the entire public records process to individual legislators,” the North Carolina Open Government Coalition wrote on social media. “Interpreted narrowly, it gives legislators more power to determine when their records go to the State Archives for permanent storage. This greatly risks depriving the public of historical information when each individual elected member decides for themselves what should be public.”

The response from state lawmakers: Adding in additional provisions to make the General Assembly even less transparent.

Not only did lawmakers keep the draft budget language, they added new provisions into the budget conference committee report to repeal a statute granting the public access to redistricting documents. They also added provisions declaring current and former state lawmakers “the custodian of all documents, supporting documents, drafting requests, and information requests” and said lawmakers weren’t required to disclose any records.

Effectively, the final budget language granted lawmakers total control over information that ought to be public. And the language came out just 18 hours before an initial floor vote was scheduled, catching Republican and Democratic lawmakers alike by surprise.

“When they add in provisions that say that you can destroy or sell your records, then they’re adding explicit permission to be corrupt,” Meyer told me in an interview. “Corrupt, either in destruction of records that would allow either the court of law or a court of public opinion to hold you accountable. And in the case of selling your records, actually allowing you to profit from withholding your records from public view.”

Which takes me to my request…

Making the request

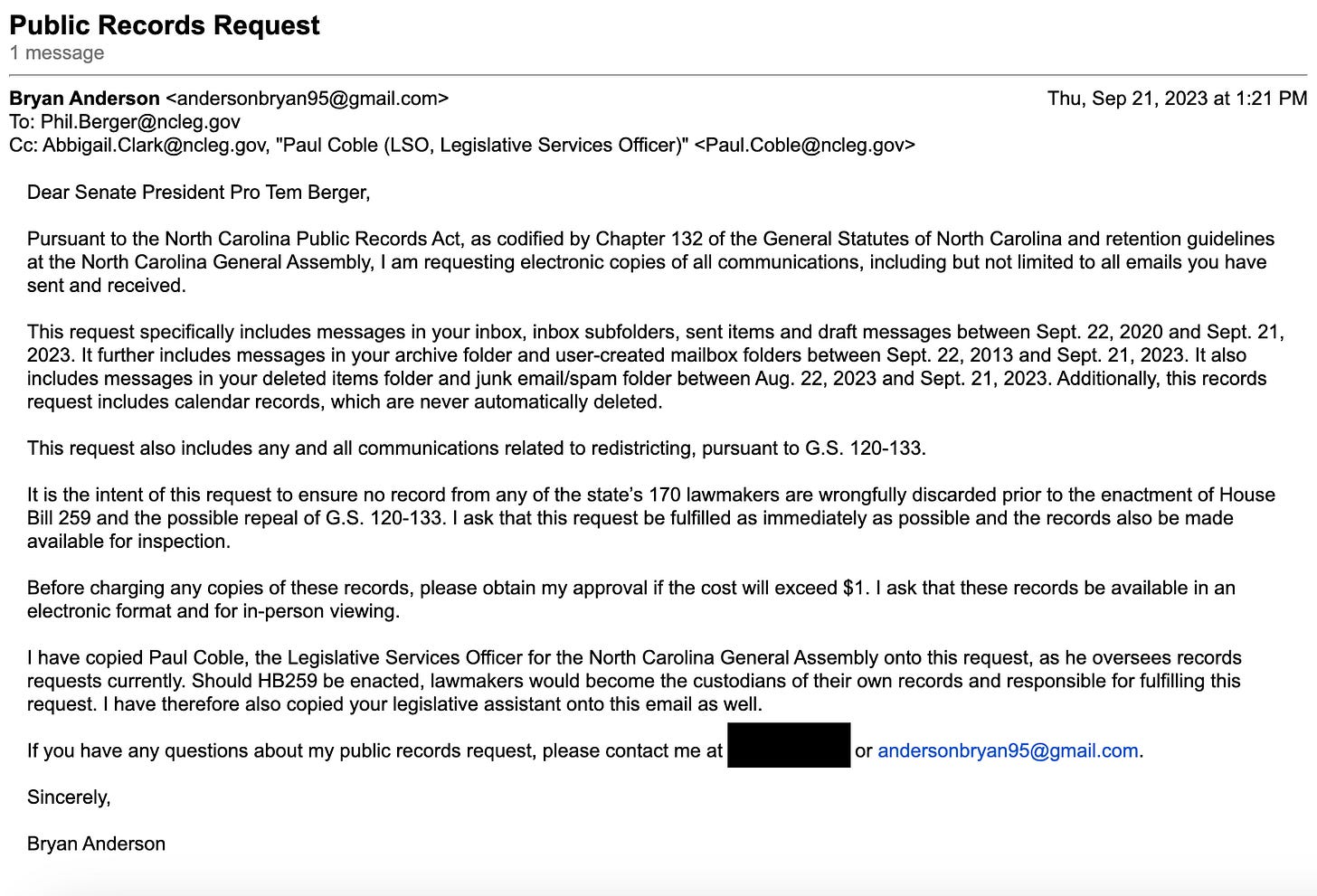

After lawmakers responded to legitimate concerns about transparency in the leaked budget by making the General Assembly far less transparent in the final version of the budget, I made a string of records requests the day of initial votes.

The query that received the most attention and pushback: Requesting up to 10 years of communications from all 170 state lawmakers.

The second request: Three days worth of information from budget conference committee members.

A third request was made specifically to Berger, as he had received pushback for trying to expand casinos in rural parts of the state to compete with a Virginia casino by the North Carolina border.

The central goals of these requests: To better understand what lawmakers may have been trying to withhold and why.

Who added the public records provisions into the budget?

By all accounts, the public records language was inserted into the budget by Republican Senate leader Phil Berger with the support of House Speaker Tim Moore.

When I asked the lead House budget negotiator, state Rep. Jason Saine, about the origin of the new provisions, he replied at the time, “That came from the corner offices.”

He added, “It didn’t come from House appropriators is all that I know.”

No Republican has taken ownership of the provisions being added.

But on Oct. 12, Moore told me he believed the idea came from legislative staff and Berger.

“Really, it came from staff,” Moore said. “It came from legal staff who said we needed to clean up some ambiguities in the law, that there are some gray areas. I believe that Senator Berger spoke specifically about something that had to do with Cultural Resources. There was some issue that triggered that and I don’t know the details.”

Moore added that he had no involvement in the provisions being crafted. “It wasn’t something that I was working on specifically, and it really seemed rather benign from the way it was described.”

As the budget worked its way through the legislature, Berger claimed to reporters that there was a dispute between the Legislative Services Office and the state Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, which archives public records. Berger claimed the issue was “whether or not the executive branch should have the ability to tell the legislature that certain things have to be saved in order to be archived.”

But when the Raleigh News & Observer asked the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources about Berger’s statement, spokesman Schorr Johnson said there was no such no dispute and that archives staff last answered questions from the Legislative Services Office over a year and a half ago.

“We are not aware of any dispute,” Johnson told the N&O.

Berger’s office has yet to make the senator available for an interview with me. His office has also declined to turn over any documents, with Berger’s general counsel, Joshua Yost, telling me in a Dec. 4, 2023, letter that the maximum transparency I sought was “an unduly burdensome request that is too open-ended to fulfill without requiring significant resources and associated cost” and that my narrower request for three days of records didn’t produce any disclosable communications.

Less than eight hours after I received Yost’s letter, I responded with a letter revising my request for all communications to a narrower timeframe, added specific gambling-related search terms for them to look through, and requested disclosure of the number of communications Berger and his colleagues have deleted before and after the budget’s enactment.

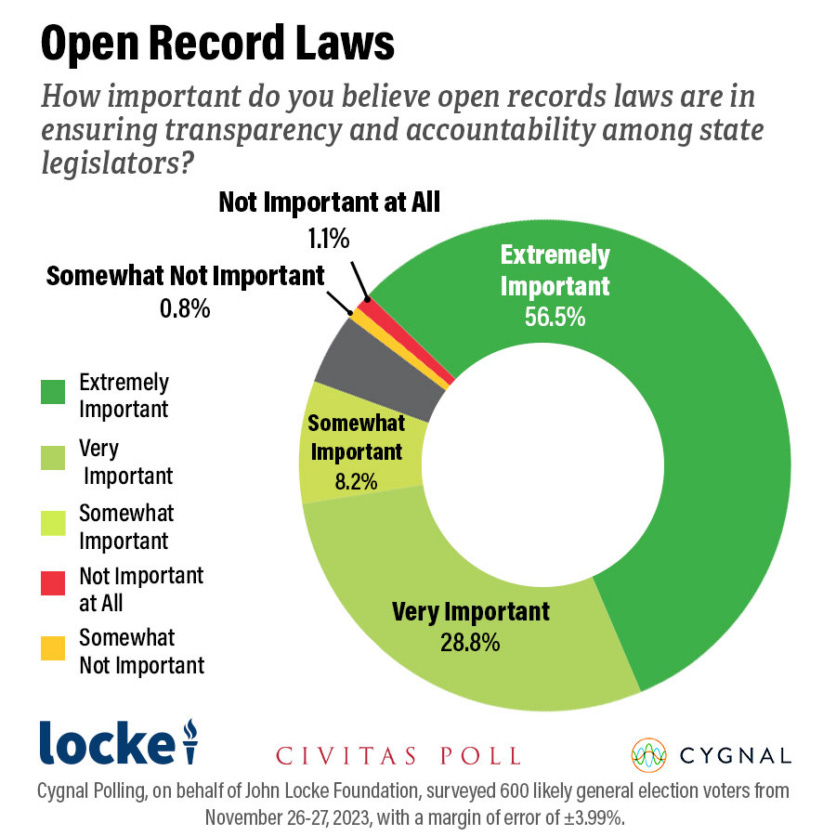

The letter noted the overwhelming view of the public (including 89% of Republicans, 93% of Democrats and 94% of unaffiliated voters) that believe state legislators should be held to the same transparency standards as other public officials under open records laws, according to a John Locke Foundation survey of likely voters. I further highlighted a note Berger’s office shared in 2021 that said, “Elected officials should not be given special treatment just because of their title or office.”

More than four months later, Berger’s office hasn’t provided an update to the revised request.

Meyer’s story

Over the course of almost six months, Meyer and his staff worked intermittently to better understand the General Assembly’s public records process and how best they could go about disclosing the maximum amount of information possible.

For Meyer, he wanted to show the absurdity of the state’s system.

“It's a matter of principle,” Meyer said. “The public should have access to everything that we do when they elect us and they pay for us. I don't understand any need to compromise on that principle, unless you're compromising on other principles. And I want to show that I'm not.”

A staff member estimated they spent at least 40 hours compiling Meyer’s emails, navigating the state’s records system and uploading it onto a thumb drive.

Meyer said many of his legislative colleagues use their personal email to circumvent public records disclosure, but that he relies heavily on his legislative email to converse with colleagues and constituents.

Because I made my records request before the budget took effect, Meyer said he sought clarity from Paul Coble, the General Assembly’s Legislative Services Officer, on how best to proceed with my request.

“Coble was no help,” Meyer said. “You can see the emails and you can see he's kind of a standoffish jerk. And what we were directed to do was to coordinate with the ISD person [Information Systems Division network administrator Lynn Carter] that's assigned to work on this. It's one staff person who does all the public records requests and all subpoena requests and probably has other parts of her job.”

When I asked Coble to help coordinate the disclosure of lawmakers’ records dating back to Jan. 1, 2023, he replied, “I like this one. ‘Since you are going to cut off public records requests when the budget is signed into law, give me everything including the kitchen sink now and everything you can anticipate to be written in the future.’”

Meyer said there is now no longer any independent staff guidance beyond a 2021 records retention policy.

Lauren Horsch, a former Raleigh News & Observer reporter who is now a spokeswoman for Berger, said it’s not Coble’s job to facilitate the release of public records.

“Members of the General Assembly are the custodians of his or her own records.” Horsch wrote in an email to me. “This has been the longstanding policy and was not altered by any legislative change this biennium. To my knowledge, Mr. Coble has never released a member’s emails because he is not the custodian of that member’s records. It is likely that you have not received a response to this request because it was not sent to the correct records custodian.”

Meyer blames Coble for contributing to the decline in the legislature’s transparency.

“If you're a citizen and you want to know how do I exercise my constitutional right to petition my government, the rules of how you get to do that are all dictated by Paul Coble. And it appears that the only people that he is accountable to in setting those rules and enforcing them are the Republican legislative leaders of each chamber.”

Meyer added, “The General Assembly should be funded and staffed in a way that makes sure that we are compliant with the public records law, which now is easier because we don't have to be.”

Meyer largely handed off the records request to a staff member, who worked with the Information Services Division to process the request and get advice on sorting through emails and exporting them.

In the end, 142,675 emails were disclosed.

What’s in Meyer’s emails?

Meyer’s emails are largely routine communications about legislative processes, media interviews and constituent issues.

While you may be surprised to learn I haven’t been able to pour through tens of thousands of emails, there were some quirky finds.

Perhaps most notable was Meyer criticizing a fellow Democratic lawmaker for saying she couldn’t help an organization run an amendment to a 2022 budget appropriation that Republicans gave to crisis pregnancy centers.

In an email, Lynne Walter, advocacy and organizing manager for Pro-Choice NC who describes herself on LinkedIn as “100% pro-abortion AF!,” asked Rep. Deb Butler and others for help in directing funds away from anti-abortion groups.

Butler replied, “To my knowledge since the budget has been passed, I don’t believe an ‘amendment’ is in order at this time. If others think it feasible, I’m happy to participate, but probably the only mechanism is a separate appropriation which I don’t imagine we have time to accomplish because my understanding is that the short session is expected to be very short. I await ideas from my colleagues and I’m happy to help as necessary.’”

When Meyer was forwarded Butler’s response, he told Walter, “That is a bullshit answer she gave you. It shows that she doesn’t understand the process nor the strategy.”

Earlier this year, Meyer said he opposed a GOP appointments bill in part because it tapped Republican strategist Jim Blaine for a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Board of Trustees seat. Meyer called Blaine and others “problematic choices.”

In a January 2021 exchange with an Orange County parent, Meyer voiced his frustration over educational learning loss and the pace of school reopening. Meyer also noted how he didn’t think Gov. Roy Cooper would force districts to reopen.

“I truly share your concerns about children being out of school,” Meyer wrote. “I have talked with our local school boards about trying to get students back as soon as possible. And I really believe that we should be prioritizing opening schools over all else besides keeping hospitalizations down. That said, I do not think that the Governor will likely force schools to go back into session. I’m not even sure that he [h]as the authority to do that. I think the best place for your advocacy is the school board. I know they haven’t yet made the decisions that you would like, but they have many further decision points coming and do need to hear from constituents.”

In 2021, Meyer also grew fed up with Drew Edwards, the current president of the North Carolina Democratic Party’s labor caucus.

Edwards sought to set up a meeting with Meyer, but appeared to grow insulted after a Meyer staff member offered a list of days and times for Edwards to choose from. Edwards then threatened to relay his concerns to party leadership and withhold a labor endorsement and gave his contact information for Meyer to call him.

Meyer then sent a note a party leader, writing, “This guy is coming off as a class one asshole, and I’m not interested in talking with him. I don’t want to make our relationships with labor any harder than they are. So let me know if you think there’s something else I can do. If not, I’m moving on and forgetting about this guy.”

Will anything change?

Republican leaders have said they don’t foresee making any changes to the newly revised public records laws.

“I don’t see us making any changes to it,” Moore said on Oct. 12. “And, really, I think a lot more noise has been made about this really than is warranted. … As a practical standpoint, there’s really not a change. … We already have legislative confidentiality that keeps a lot of these things out. We will routinely though, if we think there’s a good reason, send over records that are confidential under the legislative privilege. But as a material matter, there’s been a lot more noise about it than what it really does.”

In the meantime, there remain little to no incentives for transparency. Many lawmakers have little bandwidth within their offices to respond to records requests, while others disregard requests entirely.

Meyer and a handful of other Democrats may seek revisions through a bill amendment or budget technical corrections process, but those efforts are highly unlikely to succeed.

“I will likely try and introduce language where possible to repeal these changes, and maybe even to introduce a stronger public records law,” Meyer said. “I haven't started on that yet. But that's something that I would be interested in doing. I know that that won't pass under the current legislative leadership. But I think it's important to do.”

Meyer said he’s had conversations with a handful of Republicans who privately dislike the budget’s changes to public records laws but are likely unwilling to buck the party.

“All indications are that they're going to let Berger and Moore get away with this, in part because they're going to benefit from it and the public is not,” Meyer said.